Ocean Winds enter Irish offshore market with a combined 2,300MW bottom-fixed projects

5th October 2021

At Calor, we aren’t just on a mission, we are leading one

5th October 2021Renewable energy acceptance

Credit: Aparajita Banerjee

University College Dublin’s Geertje Schuitema discusses the importance of a bottom-up approach to renewable energy development in securing community acceptance.

Discussing current levels of community acceptance to renewable energy development in Ireland, Schuitema points to a mindset shift which appears to be moving away from an automatic perception of community acceptance being linked to objection, to one of greater support.

On the definition of acceptance, she says: “The reality is that social acceptance of energy is not a fixed measurement and in fact, is dynamic. Attempts to gauge social acceptance of renewable energy development often fail to recognise that not only can overall attitudes change but attitudes to certain aspects, components or technology can also change.”

Instead, Schuitema believes it more efficient to not gauge the acceptance levels of renewable energy development but instead to analyse under which conditions are people more willing to accept certain types of renewable energy development and the process that underpins it.

Such analysis was the aim of Schuitema and her research team in a recent project conducted in the Midlands, a key area of focus in the current energy transition. In 2018, Bord na Móna announced its decision to close 17 active bogs by 2020 and the remaining 45 within seven years. In 2018, the Midlands Regional Transition Team (MRTT), established in response to the acceleration of Bord na Móna’s decarbonisation programme, estimated the loss of 2,000 direct jobs and a further 2,000 indirect jobs.

Schuitema’s research project focused on Lanesborough, County Longford an area where peat production ended this year and for which An Bord Pleanála consented planning for Derryadd Wind Farm in June 2020, including the development of 24 wind turbines.

Setting the context for the research, the academic points out the potential broader social implications for the local community in relation to the closures, not least on workers, their families, their households, and the wider community.

As well as a focus on the perception by workers of the transition process, the pre-pandemic study also looked at how the wider community viewed the development of their region, as part of the transition, and how acceptable they found different proposals to develop country.

Schuitema explains that initial research in the area through a series of interviews painted a picture of little support for the planned development of wind turbines and wind energy in the area. Instead, they were met with proposals which included support for a wilderness park or for solar energy development.

“These bottom-up proposals, where the community themselves had thought about how to best develop up the region, enabled us to develop a survey whereby we compared the existing proposals (described as a top-down proposal) to an alternative development mooted by the community (bottom-up proposal).”

The survey was an evaluation of two potential future developments. The bottom-up proposal was for a Mid-Shannon wilderness park with solar panels compared to the Derryadd wind farm proposal. Given the remoteness of the area, a paper-and-pencil survey was conducted in the Lanesborough community in February 2020. A total of 181 people took part in the survey which had a 31.9 per cent response rate.

Explaining the survey, the academic says: “We wanted to assess which of the developments were more acceptable to the local community, but we also wanted to understand the reason that there might have been a difference in acceptance levels, recognising that bottom-up developments often may not fit with the national plan or be realistic, for various reasons. It was important to understand the underlying motivations.”

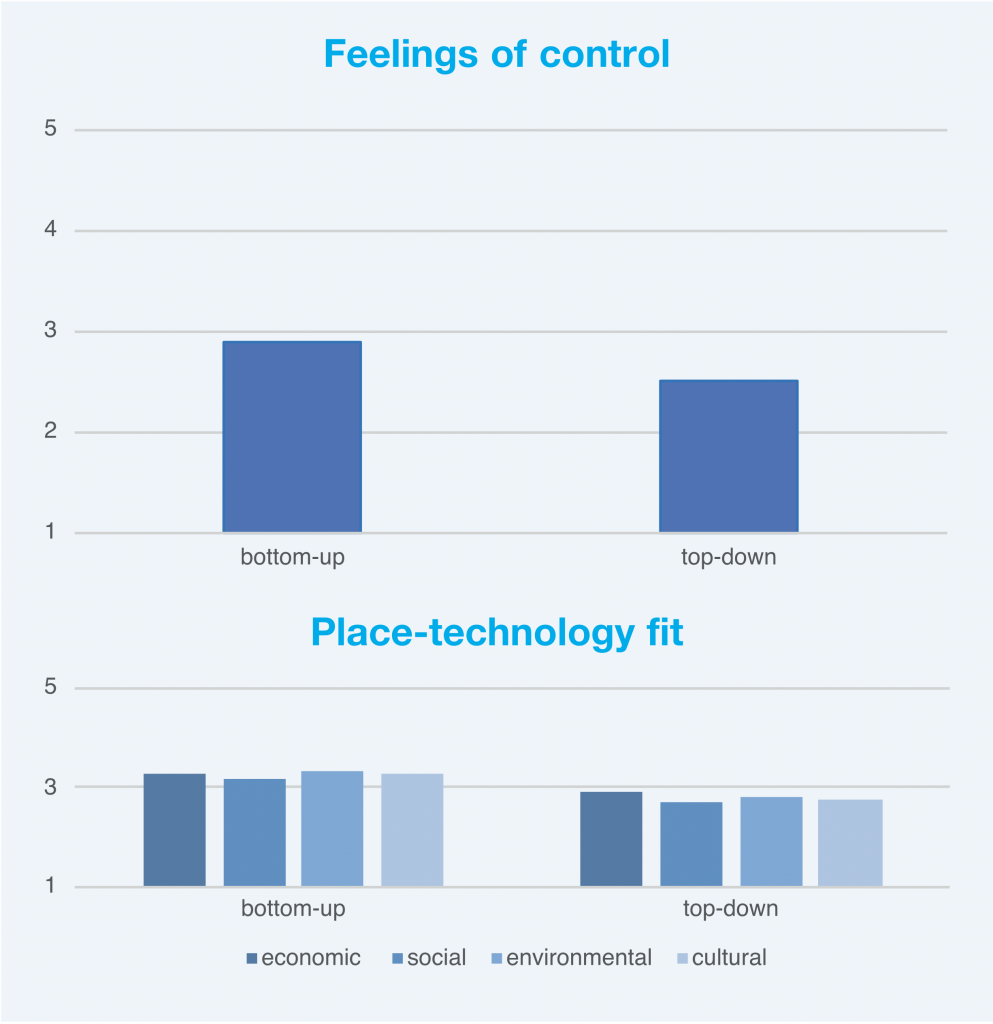

Understandably, acceptance levels for the bottom-up proposal were above that of the top-down development. Schuitema acknowledges that such a finding does not factor in feasibility or linkage with national ambitions, however, the study also highlighted that one of the main reasons for greater acceptance of the bottom-up process was an element of control.

Schuitema says: “The findings are an illustration that people very much like to feel heard and to feel like they have control over the decisions that are taken within their community. Keep in mind that this is a community that already has fears over the closure of peat power plants and so they already have experience of decisions being made on their behalf. In relation to development, there is evidence that communities want influence.”

A further aspect explored by the team was in relation to psychological ownership, which refers to a collective feeling that a development belongs to a community. Psychological ownership does not have to include physical ownership but is more about ownership of the concept.

Again, a bottom-up approach, when compared to a top-down approach, provoked a stronger feeling of psychological ownership over a project.

“The finding that greater levels of ownership are provided by a bottom-up approach is important when you consider the first RESS auction’s inclusion of seven community projects and ambitions to increase this further in later auctions. Public buy-in to the energy transition is a critical ambition of Ireland’s decarbonisation agenda and increased acceptance through bottom-up approaches to renewable energy development should be given consideration,” Schuitema says.

Finally, the research sought to explore the two hypothetical projects, with their different approaches, fitted with the community. The question was asked within the four dimensions of economic, social, environmental, and cultural, and as the findings below show, in each dimension, the bottom-up project approach was assessed as more fitting.

Schuitema concludes: “The context of the study is important. We have an area where a just transition plan is in place but at the same time, it was clear that people in that area did not always feel that that plan matched with their own ideas of that it fitted them.

“It showed that the way people were treated in terms of a just transition was a pre-condition for how acceptable they felt renewable energy developments were.”

Posing the question: Under which condition is renewable energy acceptable, Schuitema says that the research would signify the key elements are:

- allowing influence in the decision-making process and change;

- building a sense of collective ownership of project and alignment with community identity;

- use of fair and just procedures; and

- stimulating and building on community led approaches is a mean to achieve this.

Geertje Schuitema’s research is currently under review in the British Journal of Social Psychology.