The role of innovation in the energy transition

8th December 2020

Driving Ireland’s green recovery

8th December 2020Efficiency, renewables and interconnection

The Programme for Government signalled a move away from ambition to action as Ireland seeks to move from laggard to leader in the renewable transition, writes David Whelan.

In June 2019, the European Commission, in assessing the draft integrated National Energy and Climate Plan of Ireland out to 2030, made a number of recommendations, which essentially boiled down to a need for greater development in efficiency, renewables and interconnection.

Not surprising then, was a core focus on these areas as the newly formed government delivered its climate-focused Programme for Government (PfG), almost exactly one year later.

The Programme for Government has evolved in the context of Ireland not making enough progress on climate in action recent years. In energy, the challenges of overreliance on imported fossil fuels and a weakly interconnected electricity system have not been helped by the absence of a robust policy framework and, until recently, enough political will.

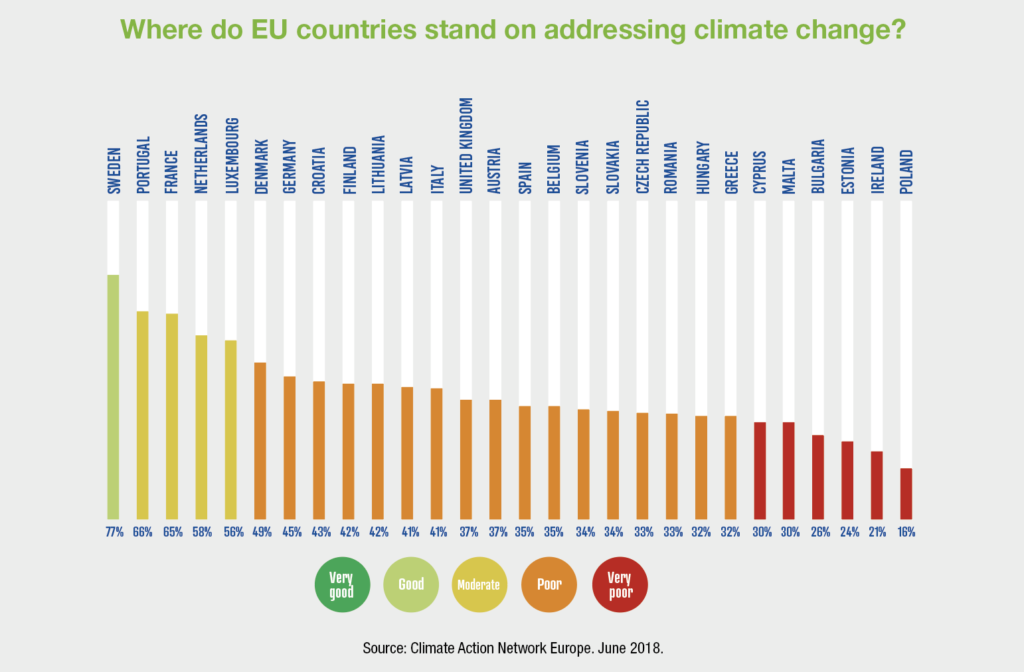

In April 2020, the SEAI, the national energy authority, highlighted that not only was Ireland not on track to reach its 2020 targets but that it had the second lowest progress to meeting the overall Renewable Energy Supply (RES) target of all EU member states. Although some progress has been made on the data collected from 2018, including the publication of Ireland’s Climate Action Plan, SEAI highlighted a 5 per cent gap to the 16 per cent of gross final consumption of renewable energy target.

The Climate Action Plan, looking out to 2030 and beyond to 2050, was a direct response to these failings. However, while the plan delivered the required signals around injecting fresh emphasis into the renewable transition, the delivery of a cross-departmental enabling plan has proven more difficult than was perhaps initially estimated.

The Programme for Government has sent a strong message that Ireland is refusing to continue being a laggard on climate action. In establishing a pathway to net zero by 2050, the importance of the decarbonisation of energy is recognised through significant pledges.

Emission and energy targets

Probably the most significant undertaking that government will push ahead with the 70 per cent renewable electricity target by 2030, set out in the Climate Action Plan, while also producing a ‘whole-of-government’ plan setting out how it will deliver on this. Importantly, this will look at not just the methods of renewable generation but also development of things like a skills base, supply chains and legislation. The decarbonisation of energy coincides with an enhanced target of a 7 per cent reduction in overall greenhouse gas emissions annually out to 2030, a 51 per cent reduction over the decade. Interestingly, some have suggested that this enhanced target could have gone further when factoring in the implications of the fall in economic output brought about by Covid-19.

“In energy, the challenges of overreliance on imported fossil fuels and a weakly interconnected electricity system have not been helped by the absence of a robust policy framework and, until recently, enough political will.”

The ambition to achieve net zero carbon emissions by 2050, in line with heightened ambitions from the European Commission in its Green Deal, will be included in law in the form of the Climate Action and Low Carbon Development (Amendment) Bill 2020, which will define how new five-year carbon budgets will be set. Alongside this will be a newly established Climate Change Advisory Council, with a strengthened role to advise and propose carbon budgets to government.

The Programme for Government also set the timeframe for the first Renewable Electricity Support Scheme (RESS), providing a route to market for the first new onshore windfarms of the 2020s, solar projects at scale and a small number of community projects. Auctions are now set to be held annually, with a dedicated offshore auction planned for 2021.

Carbon tax

The Climate Change Advisory Council recommended a €35 per tonne tax for Budget 2021 from €26. Instead, the Government opted for a €33.50 per tonne price but outlined a desire to see it rise to €100 by 2030. The Programme for Government has enshrined this rise by outlining a need for a €7.50 rise per annum until 2029 and a €6.50 rise in 2030.

Whether the carbon tax increase will be enough remains to be seen. The rise to €100 by 2030 was seen as a way of incentivising the use of renewable fuels and reducing fossil fuel usage in an affordable manner, however, the pandemic’s impact on lowering the cost of fossil fuels may lessen the competitiveness of greener alternatives.

This may also have an impact on the projected revenue the carbon price increases are set to generate. €9.5 billion is estimated to be generated over the next decade, with plans to use €3 billion to mitigate fuel poverty and €5 billion to part fund a national retrofitting programme, with particular focus on the midlands region and on social and low-income tenancies.

Energy efficiency

Decarbonisation will not be achieved by renewable generation alone. Even reaching the ambitious target of 70 by 30 will mean a 30 per cent dependence on imported fossil fuels. The Government recognises that in order to meet net zero by 2050, the transition to renewables must be done in parallel with a reduction of energy consumption. To this end, an envisaged National Energy Efficiency Plan is seen as the missing piece of the jigsaw in the Government’s transition ambitions, setting higher targets for all sectors.

A major focus for energy efficiency is in the are of heat and in particular, on domestic heating. Amidst a broad portfolio, Minister Eamon Ryan has privately indicated to the energy sector that his two major project priorities are offshore wind and retrofitting. This will be aided by a pledged National Retrofitting Plan, part of the National Economic Plan, which will target 500,000 homes by 2030 through a new area-based approach. Additionally, the Energy Efficiency Obligation Scheme is to be amended to increase the obligation target on delivering parties, boosting the supply of retrofits.

In targeting heat, the Government says that it is to launch a scaled-up programme for district heating and more importantly, as far as the consumer is concerned, develop a suitable regulatory environment. However, firm commitments in this area are scarce, with the PfG saying that a feasibility study will be carried out on the need for “a district heating authority and setting new targets for district heating as part of a new strategy”.

Energy efficiency in domestic homes is also the main target of a move away from all mechanical electricity metres to smart metres by 2024. Outside of the domestic market, greater efficiency is also set to be met by the introduction of an at least 50 per cent decarbonisation target for the public sector and the Government is set to install efficiency standards that will seek to address the growing use of power in growth areas, particularly, data centres.

Offshore energy

Developments in the ambitions for offshore have been the defining feature of the Programme for Government, evidencing a switch from ambition to action. As well as a pledge to host a dedicated offshore RESS auction in 2021, a raised target of 5GW of offshore wind by 2030 is a major boost to market confidence and will serve as a kickstart to the industry in Ireland.

Development of offshore wind generation is complicated and in establishing an enabling environment for progress, the Government has stated its desire to give priority to a Marine Planning and Development Bill and Ireland’s first ever marine spatial planning policy and framework, comprised in ‘Project Ireland Marine 2040’.

Interconnection

Although it is an existing commitment, the PfG has restated the Government’s intention to support the Celtic Interconnector, linking Ireland to Europe’s energy grid. This interconnection is a seen as vital if Ireland is to take full advantage of its ambition to be a leader in renewable energy by allowing the export of excess renewables. The value of this is recognised in that the Government is to commence planning for future interconnection.

As new technologies develop to scale, accompanied by envisaged greater levels of microgeneration, how power is managed will become increasingly important. Storage at scale has long been identified as necessary if the maximum value is to be attained from generators. The PfG has promised to strengthen the policy framework to incentivise both electricity storage and interconnection. The incentivisation of storage will complement a major increase in large scale solar projects coming online in the next few years. As well as the success of over 60 solar projects in Ireland’s first RESS-1 Auction, the Government is to develop a solar energy strategy for rooftop and ground-based photovoltaics to ensure solar plays an even greater role in the energy mix.

Onshore wind will continue to be the main source of renewable electricity on the grid out to 2050 and beyond. In recognising the need for a greater energy mix if Ireland is to decarbonise, the Government is to finalise the Wind Energy Guidelines. Progress in this area has been slow given the significant opposition from generators around the restrictiveness of the proposals. The Wind Energy Development Guidelines (WEDGs) were issued for public consultation in December 2019 and the new proposed guidelines were met with much opposition. Central to this opposition was a blanket approach to noise limits, which generators say will not only severely hamper any potential future builds but also restrict the re-powering of existing sights, putting Ireland’s ambition for increased renewable electricity generation in doubt. Undoubtedly, the Government’s draft guidelines will require amendment prior to publication.

While solar and wind are seen as the main vehicles to achieve 2030 targets, the future potential of bioenergy and green hydrogen to become market competitive have also been acknowledged. The PfG pledges to “rapidly evaluate” the potential role of sustainable bioenergy and invest in research and development in green hydrogen, as a fuel for power generation, manufacturing, energy storage and transport. The Government is to conduct a feasibility study into establishing a green energy hub in the midlands, utilising the existing infrastructure currently supporting peat.

Conclusion

The Government, through its climate-based Programme for Government has signalled its intention to rapidly accelerate the development of renewable energy. In the context of failing to achieve its 2020 ambitions in this regard, an effort to shift Ireland from laggard to leader in less than a decade is a significant ask. While the Programme for Government has acted as a signal of intent and serve to drive confidence in the energy sector, of greater significance are the frameworks and policies developed to support these ambitions. The Government has grasped the opportunity that lies in getting out in front, in terms of the race to carbon neutral by 2050 occurring across Europe but must act to enable the transition.